Red Sorghum, director Zhang Yimou’s 1987 debut film, is rooted in 1930s rural China, notable for its innovative visual style and profound cultural themes. Adapted from Nobel laureate Mo Yan’s novel, a young woman sold into marriage has to lead a rural sorghum wine distillery and its workers, contesting through bandit danger and Japanese invasion, all set against the backdrop of northern China’s vast sorghum fields. The film centres on a young woman, Jiu’er, who takes over her late husband’s sorghum winery, navigating love, tradition, and upheaval as bandits and Japanese forces reshape the world around her. It employs a unique off-screen narration from the viewpoint of the protagonists’ grandson, blending family history and fable with eruptions of raw violence as World War II intrudes, culminating in brutal scenes illustrative of historical trauma.

Upon its release, the movie was hailed for its visceral beauty and departure from socialist realism, revolutionising Chinese film both in China and abroad. Over time, critical scholarship has highlighted its subtextual critique of feudal values and war, as well as its nuanced portrayals of gender and community. Today, it stands as a landmark, defining the “Fifth Generation” movement and cementing Zhang Yimou’s reputation for fusing Chinese folk culture, audacious style, and universal emotion. Widely celebrated, it won the Golden Bear at Berlin and marked a turning point in Chinese cinema’s global reception.

Femininity and Individualism

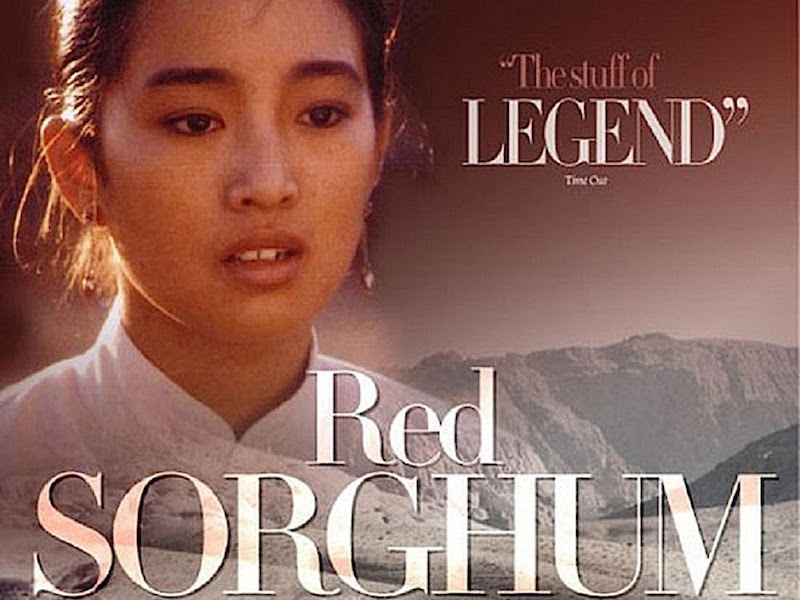

Gong Li presents Jiu’er as a figure of strength and independence in her first major role. Breaking conventional cinematic “male gaze” tropes by foregrounding Jiu’er’s perspective and desires gives her an autonomous subjectivity rarely seen in the era’s cinema. In the film a vivid example of Jiu’er’s assertion of femininity and individualism occurs when she takes ownership of the sorghum distillery after the mysterious death of her leprous husband.

One key scene illustrating her independence is when she confidently commands the winery workers, revitalizing production and inspiring collective pride. Her leadership is contrasted with her earlier role as a controlled bride. Jiu’er emerges as a new kind of Chinese heroine through this scene—independent, strong-willed, and resilient—who challenges patriarchal norms and social constraints on women. She is portrayed with liberation, courage, and determination, reflecting feminist and countercultural themes of the late 1980s. The film uses the imagery of the red sorghum fields and wine metaphorically to evoke her passionate vitality and life force. Zhang Yimou’s visual storytelling foregrounds Jiu’er’s perspective and strength, framing her as an emblem of feminine empowerment who refuses to be confined by traditional gender roles.

Folk Culture and Resistance

Zhang’s lavish cinematography and stylised rituals challenge the then-dominant realism of Chinese cinema, favouring folklore, myth, and generational storytelling. Rituals such as wedding songs, wine-making and peasant revolts anchor the story in local tradition, evoking the resilience and earthy humour of the community even amidst brutality and loss. The recurring motif of red sorghum wine establishes a sense of cultural rootedness, reflecting both ancient tradition and a spirit of rebellion.

The cinema portrays rural life not as static tradition but as a dynamic, living culture that negotiates survival and solidarity through collective memory and inherited practices. The red sorghum fields in itself become a symbolic landscape imbued with meaning, representing both fertile life and the bloodline of cultural resistance. This is why the film articulates folk culture as a powerful medium of cultural preservation and resistance, connecting human stories to broader national and historical struggles. The concept of China’s 1980s “search for roots” (寻根运动) reflects a cultural and intellectual movement during which artists, filmmakers, and intellectuals sought to rediscover and reaffirm traditional Chinese cultural identity after the dislocations caused by the Cultural Revolution and rapid modernization. This movement involved revisiting rural traditions, folklore, and historical narratives that were suppressed or marginalized during earlier decades of political upheaval.

In the movie, this is embodied in the vivid portrayal of ordinary rural people who, despite living under feudal oppression and facing foreign invasion (Japanese occupation), are depicted with fierce vitality, resilience, and primal energy. Jiu’er and the community’s collective resistance to bandits and invaders symbolizes both a literal and figurative reclaiming of agency. This resonates with the 1980s counterculture’s desire to break away from oppressive, official narratives and re-engage with authentic popular traditions, emotions, and struggles. Considering China’s 1980s “search for roots” and counterculture ethos, the film celebrates the conviction and primal energy of ordinary people facing feudal oppression and foreign occupation.

Symbolism through themes of Red

Red, in particular, is used to construct rich contextual layers: joy and celebration during rituals, menace and tragedy during violent turns, and ultimately a unique “red culture” that ties the fate of individuals to that of the nation. It is aestheticized through fields, wine, costumes and ritual, reflecting life and death in northern rural China. It also signals primal human desire, freedom, blood, and fate, aligning personal stories with national identity and collective memory. Zhang’s vivid cinematography also balances celebration of rural life with moments of brutality and loss. The colour’s layering signifies physical passion, violence, and broader cultural meanings in the Chinese context, including prosperity, revolution, and national identity. The red sorghum fields, the red bridal sedan, and the red wine all serve as manifestations of Jiu’er’s liberation from feudal constraints and forced marriage. Her illicit love in the sorghum fields, combined with the vibrant red imagery, visually communicates her breaking away from conservative social norms and asserting her own identity. Through these techniques, Zhang Yimou’s colour use beautifies his films and becomes an indispensable tool for storytelling and symbolism. Zhang’s colour choices become a non-verbal participant in the narrative, assisting in revealing character moods, highlighting moments of conflict, and distinguishing key plot shifts. The colours used by Zhang in his films are meticulously chosen to reflect both traditional Chinese aesthetics and to give viewers non-verbal cues about the story’s emotional and historical context.

The film resists explicit moral judgments about its characters or the period, instead offering an almost surreal, allegorical vision of strength and survival as China was redefining itself in the 1980s. Notable scholars such as Zhang Xudong, highpoints Zhang Yimou’s narrative features contextualized within China's history. Film theory researcher, Lin Yan discusses the groundbreaking visual storytelling and use of Chinese imagery in the film. Senses of Cinema lauds the film for its "unique narrative style and innovative use of Chinese imagery" that challenged traditional conventions and set new standards in Chinese cinematic expression. Scholars and critics have lauded its dramatic style, symbolic imagery, and complex portrayal of rural China, noting how its lush visuals and unconventional heroine signal a break from socialist realism while challenging traditional norms. Red Sorghum is a powerful exemplar of cinematic artistry and cultural memory and is considered one of Zhang Yimou’s most influential works.

Author

Yasheeta Sulakhe

Yasheeta Sulakhe was a Research Intern at the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). She holds two master’s degrees: one in International Relations & Strategic Studies from the University of Mumbai. She is currently pursuing another in China Studies at Somaiya School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Somaiya Vidyavihar University. Her academic focus spans India-China relations, comparative political thought, and the impact of classical strategic texts like Sun Tzu’s Art of War and Kautilya’s Arthashastra on modern foreign policy. Her research interests also include contemporary China, climate change and territorial disputes in South Asia. She has participated in the Chinese Bridge Indian Youth Delegation Program and cleared three levels of the Mandarin HSK exam. Outside academia, she is an experienced volleyball player and coach, and holds an NCC ‘C’ Certificate.